Photo © Carolina Chiarella

|

|

|

Many of the designers you’ve met in this series come from South America; but few have led as cosmopolitan a life as this month’s interviewee. He was an art director in Buenos Aires, studied type design in Europe, and was a professor in Mexico. The name of his foundry PampaType must therefore be understood as a tongue-in-cheek choice — because rather than a gaucho from the pampas he is a man of the world with literary tastes and a curiosity for all things cultural. Several of his typefaces refer to extraordinary men of letters, or their books: Borges, Arlt, Perec, Rayuela. His letterforms are striking and adventurous; simultaneously useable and great fun. Meet Alejandro Lo Celso, our man in Córdoba, Argentina.

|

|

|

Alejandro, your professional history sounds like quite a trip: you studied in Argentina, in the UK and in France, then worked in Mexico, and you’re now back in Argentina. How did it all begin?

Family influences, I guess. My mother’s mother was a pretty good calligrapher and loved literature. My mother is a historian but also an amateur painter, and used to illustrate the covers of our early schoolbooks with flourished gothic letters. From my grandfather and father, both architects, I received an all-encompassing concept of what designing, planning and living is about. In other words: the Renaissance idea that a guy has the right to be curious about everything in the universe. I was a shy kid, played alone a lot, and grew up surrounded by books. By the age of nine I had already read most of Jules Verne’s stories. These conditions instilled in me an unconditional love of books.

As a child I was intrigued by how we read. I don’t mean the technical aspect of legibility, but the more abstract and simple idea that a word (spoken, written, printed, read) points to a thought or a feeling. There has always been a material and an immaterial side underlying human experience, and I’ve always been curious about how these two dimensions interact.

After secondary school I studied film-making for some months; this had to be interrupted for a year of military service. Afterwards I switched to a two-year graphic design course in a small private school. Finally at 21 I decided that I must move from my home town Córdoba to Buenos Aires and attend the more formal Graphic Design course at the University of Buenos Aires. I was lucky to be invited by Rubén Fontana, the renowned graphic designer and type designer, to assist him by cataloguing the books in his library. This was my first exposure to the significant names and stories in the typographic world that would later become familiar to me.

While at university I had a career in the graphic media, art-directing newspapers and magazines. I already felt that I would eventually look for other landscapes. Thus in 1998, at 28, I found myself spoiled by high salaries, tired of a life that was too intense, both culturally and emotionally, and fed up of working in the media — but still full of enthusiasm about learning new things. I came across the curriculum of the MA course in type design at Reading University (UK) and immediately fell in love with the idea. I sent my papers plus an amateur font I’d been working on (a terrible slab serif that I’d like to revisit one day), and was accepted.

What was Reading University like in 1998?

The MA in Type Design was brand new. My only classmate was Vince Connare, who had just left Microsoft. Together with part-time student Conor Mangat we were the first generation, the Guinea pigs!

British universities are demanding. You really have to work like hell, discipline is their strength. I found the social interaction in campus even more stimulating. I made friends with people with professional specialisms that were very different from my own, and their presence became as important as my academic duties.

The Department of Typography’s staff was a singular discovery. Michael Twyman, the emeritus professor and former head, used to make monthly exhibitions at school with the most incredible 19th century lithographs from his personal collection. James Mosley’s lectures on type history were exquisite, and way surpassed the usually superficial information you get in books. I’ll always be grateful to him for opening new doors in my historical research.

The most impressive teacher I had at Reading was Michael Harvey. His stone-carving workshop was a foundational experience for me. It was very sad to hear about his recent passing. Mary Dyson’s seminars on legibility research opened my eyes with intriguing scientific discussions, and Paul Stiff’s solid presentations from his information design perspective also broadened my curiosities. From Gerard Unger I liked the singularity of his ideas on type design, and I especially enjoyed his passionate viewpoints of the work of designers he admires, like W.A. Dwiggins and Roger Excoffon.

Towards the end of my course Christopher Burke, the director of the MA program, introduced me to the fine editorial designer Simon Esterson in London. Simon hired me to help him design a newspaper for the Financial Times. The paper never materialized, but I learned so much from him and his team. After that project was terminated he took me to a pizzeria and invited me to join his studio. I couldn’t believe it. Two days before I had been informed that I had been granted a place in the Atelier National de Recherche Typographique (ANRT) in Nancy, France, an exceptional opportunity I could not let go. So unfortunately I had to decline Esterson’s invitation.

|

|

|

|

|

And so you went to study at the ANRT in Nancy, France.

At the time the ANRT was directed by the well-known Swiss typographer Peter Keller. It was a unique situation: we were five international students all sharing a huge, fully equipped atelier at the top of a Beaux-Arts building, with a typographic library, a free internet connection (in the year 2000!), a copy machine and the most important thing, a key to the door. We had a whole year to focus on with our individual projects. We didn’t have formal classes; advancing our projects was entirely up to us, and teachers came from time to time to give their opinions, and to have dinner and drinks with us. This trust in our independence was perfect for me after the very rigid academic year at Reading.

Among the visiting professors, the Swiss type designer Hans-Jürg Hunziker was the most significant. He was designing the typeface for the Siemens corporation at the time, and would bring his beautiful film prints of his work in progress. He’d ask us, his students, for our opinions. Can you believe that? He is a master designer, but what he taught us was humility — a rare virtue nowadays.

Sadly, the ANRT went into inactivity after Peter’s retirement (and, soon after that, his passing away). The good news is that it was recently relaunched under the direction of Thomas Huot-Marchand.

After graduating as a type designer, you worked in Mexico for many years. What was it that appealed you about Mexico?

Mexico is an incredibly rich mixture of cultural expressions, combined in ways that open your eyes to new perspectives. I lived in Mexico for eight years, and it still feels like home every time I visit. I moved there in 2001, when I was hired as a professor at the Universidad de las Américas Puebla in Cholula, in the Puebla district; four years later I joined a research and design center named CEAD.

In 2008 I moved to Mexico City as a freelance designer. I designed a custom type family named Periodista, which was commissioned by the magazine Expansión. Oscar Yáñez, its art director, invited me to join the Círculo de Tipógrafos, a group of type enthusiasts, many of whom were ex-students of mine. At the Círculo we did some interesting projects, such as the creation of a suite of typefaces based on the lettering work of Dutch graphic artist Boudewijn Ietswaart. This turned into a significant exhibition at the ATypI 2009 conference.

During those years in Mexico, I was lucky to be part of some of the most significant events that happened just before the general enthusiasm about type exploded in Latin America. Much of this has to do with the Tipos Latinos Biennale, the sequel to the Letras Latinas event organized by Rubén Fontana in 2001 in Buenos Aires, which now takes place simultaneously in many cities from the North of Mexico to the South of Chile, and whose selections of works have been exhibited globally by now. I had the pleasure to meet several talented students, many of whom have become good friends.

After eight years in Mexico I came back to Argentina in 2010 to join a university project in La Plata, where I met Carolina, my partner in life. Eight months ago we became happy parents.

|

|

|

|

|

What has all your traveling taught you?

Naturally your education and your beliefs all travel with you and are present in everything you do. I think my experiences have made me more aware of the cultural context of things — and I invest that back into my classes. Typography is a universe of subtle differences. So you need sharp intellectual tools in order to deal with its huge variety. Students need landmarks so they don’t get lost easily. Some are very sensitive and they get to perceive the subtleties quickly, for some others it can be difficult. However everyone can understand if you clearly explain to them how a shape relates to its context.

If one is to understand the evolution of letterforms in the west, one must build a clear map of references to follow — not only the printing types from Gutenberg onwards, but also the old national handwriting and calligraphic styles used before movable type. It seems crucial to me to relate letterforms to their context of creation and use — a point that has been put forward most significantly by Robert Bringhurst in his Elements of Typographic Style. Typography cannot escape the thoughts and aspirations of the practitioners of its time. There is a typographic Zeitgeist to each era.

Let’s focus on your own career as a type designer. When and how did you start up your own foundry, PampaType?

PampaType started as an idea in 2000 in the UK. I knew that one day I’d go back home and start a type foundry. When I came back to England in late 2001 after my ANRT experience in France, the 9/11 event froze the economy in the UK and forced me to return home. I spent a year or so in my parents’ house in Córdoba, basically designing new typefaces. So PampaType was already an ongoing project when I moved to Mexico.

After releasing the first typeface, Rayuela (Argentine Spanish for Hopscotch), I designed Quimera, a tribute to Roger Excoffon’s Antique Olive. Excoffon seems to me to be a rebellious voice, opposing the Swiss design that ruled the world in the 1960s. A wonderful thing happened. After I had mentioned in an interview that I admire Excoffon’s types — an enthusiasm received from Gerard Unger at Reading — I was contacted by Marianne Excoffon, Roger’s granddaughter. She offered me a copy of a curious exhibition catalogue from years ago, and I was later invited to dinner with the family of Excoffon’s daughter in Paris. I brought my French friend Paule Palacios Dalens, an editorial designer, and the family was interested in our proposal for a book on Roger’s work. We later had to drop the plan for personal reasons. I was pleased to see that two great books on Excoffon were published in France some years later — especially the one published by Ypsilon.

During our first decade, PampaType received growing recognition, and I am glad to see we continue to have an impact. In 2013, to celebrate the twelfth anniversary of the foundry, we were invited by the UNARTE school in Puebla to make a large exhibit of our work: we named it “Constelación Tipo”. On the opening night the school buildings and gardens were packed. It was really surprising and made me realize how many friends I had made during those intense years in Mexico.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Constelación Tipo”, an exhibition of PampaType’s work at UNARTE in Puebla, Mexico. Lo Celso: “The exhibition (ab)used an astronomical metaphor, linking the micro-universe of type with outer space. Our insights about typography, dressed in our typefaces, were displayed all over, on the walls, transferred onto the windows and floor of a 120-meters-square exhibition room. The aim was to establish a presence that would be as immaterial as possible, so that the exhibition put on display thoughts rather than objects.”

|

|

|

|

Could you briefly describe your approach to type design?

A feature of our typefaces is that they usually include fonts for text, titling, ornamental use and other uses, all under the same umbrella family. I find this challenging — building a system that must remain consistent while adapting to different applications or constraints, and expressing a given spirit in all these situations. I think this is one of the most exciting aspects of the craft: reaching an equilibrium between the systematic and the organic, between uniformity and diversity.

Another aspect of our typefaces is that they are often made with literature in mind. A face for immersive reading has to conquer balance in all the rhythmic relations between forms & counterforms, from a single Bézier curve to an entire book page. This means you need to develop a sensibility to understand all these rhythmic dimensions so that letters look beautiful individually while they remain ‘choreographically’ consistent too.

PampaType is 14 years old now. We launched a new website and started a publishing program of new types designed by talented colleagues: Berenjena by Javier Quintana, and Amster by type designer and author Francisco Gálvez Pizarro, both from Chile, were the first on the list. These designers (and friends) share my view on how a type design should be. There is a slight literary flavor to their designs as well as a very personal viewpoint in respect to the meaning of thoughts and words. Our dream is that these types will be used for significant texts, conveying significant meanings. But of course, in reality we have no control over how people will use our types. A typeface you create is like a daughter. One day she’ll come home with a boyfriend. Hopefully we’ll like him!

Are you actively scouting for young type designers? What do you want them to bring to the table when they’re interested in publishing with PampaType?

The idea is to publish original work of the highest quality in the same vein as the work I have been publishing until now. That is: families with a confident personality that can perform well in all sizes and that can also provide users with a variety of alternatives, both stylistically and functionally. We want to add tones of spiciness to the text without compromising its reading comfort. I think the only way to bring a really new type for reading into life is by reaching a new balance between expression and legibility. That is the result of a long-term, painful design process. There are no shortcuts — you cannot create a quality typeface in a couple of weeks. Letterforms are like wines, they mature with time. The deeper the view of the creator and the more committed his search, the richer the result will be.

Would you say that your typefaces have a Latin character, a “latinidad” about them? Are they in some way representative of the Latin American spirit?

“Latinidad” is an ambiguous word — the Latin language was created in Rome! — but it’s true that “Latino” is now often used for everything coming from Latin America. The digital era has given access to global technology to many people who simply couldn’t contribute their creativity before, and undoubtedly Latin America is one of those regions. Just as it happened in the US a century ago with the Bentons (father and son), Frederic Goudy, Dwiggins and Bruce Rogers, Latin American type designers woke up a few years ago, and now they’re showing they can make original contributions as well. Like those American designers a century ago, Latin Americans have a fresher approach to type design, as they are less firmly attached to tradition than, say, a European designer may be.

Of course some contributions are more original than others, some are clearly a fad, some others look for a perennial presence. What we see everywhere is a growing pace. Much of the expansion of this type enthusiasm in Latin America has to do with the aforementioned Tipos Latinos event. As a teacher in contact with the main schools where typeface design is taught I’ve seen how students gain experience and maturity pretty quickly. Some manage to contribute designs of the same quality as well-known European or American designers. These events have become important meeting places. I think the next step should be to open them up to a worldwide audience. People should not get the impression that “Latino” type design is an enclosed world.

Alejandro, many thanks for your insights and stories!

|

|

|

|

|

|

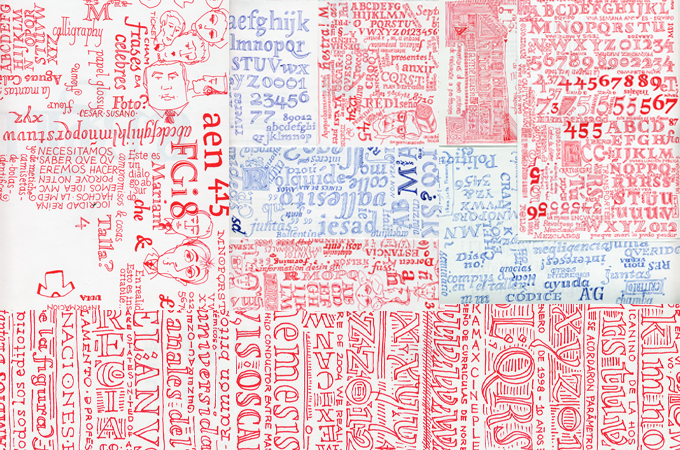

“Every Monday morning at UDLA, Universidad de las Américas Puebla we had terribly long teachers’ meetings, like 4 or 5 hours, and you couldn’t escape. In order to kill boredom I used to draw letters & things with pen and paper. I made a whole collection called ‘aburribujos’, from Spanish ‘aburrido’ = bored + ‘dibujo’ = drawing!”

|

|

|

MyFonts on Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter & Pinterest

Your opinions matter to us! Join the MyFonts community on Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter and Pinterest — feel free to share your thoughts and read other people’s comments. Plus, get tips, news, interesting links, personal favorites and more from the MyFonts staff.

|

|

|

|

Who would you interview?

Creative Characters is the MyFonts newsletter dedicated to people behind the fonts. Each month, we interview a notable personality from the type world. And we would like you, the reader, to have your say.

Which creative character would you interview if you had the chance? And what would you ask them? Let us know, and your choice may end up in a future edition of this newsletter! Just send an email with your ideas to [email protected].

In the past, we’ve interviewed the likes of Maximiliano Sproviero, Sumner Stone, Typejockeys, Charles Borges de Oliveira, Natalia Vasilyeva, Ulrike Wilhelm, and Laura Worthington. If you’re curious to know which other type designers we’ve already interviewed as part of past Creative Characters newsletters, have a look at the archive.

|

|

Colophon

This newsletter was edited by Jan Middendorp and designed by Anthony Noel.

The Creative Characters nameplate is set in Amplitude and Farnham; the intro image features Arlt Titulo Hueca and Rayuela Luz; the quote image is set in Arlt; and the large question mark is in Farnham. Body text, for users of supported email clients, is set in the webfont version of Rooney Sans.

|

Comments?

We’d love to hear from you! Please send any questions or comments about this newsletter to [email protected]

|

Subscription info

Had enough? Unsubscribe immediately via this link:

www.myfonts.com/MailingList

Want to get future MyFonts newsletters sent to your inbox? Subscribe at:

MyFonts News Mailing List

|

Newsletter archives

Know someone who would be interested in this? Want to see past issues? All MyFonts newsletters (including this one) are available to view online here.

|

|

|

|

MyFonts Inc, 600 Unicorn Park Drive, Woburn MA 01801, USA

MyFonts and MyFonts.com are trademarks of MyFonts Inc. registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and may be registered in certain other jurisdictions. Antique Olive is a trademark of Madame Marcel Olive. Other technologies, font names, and brand names are used for information only and remain trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective companies.

© 2015 MyFonts Inc

|

|

|