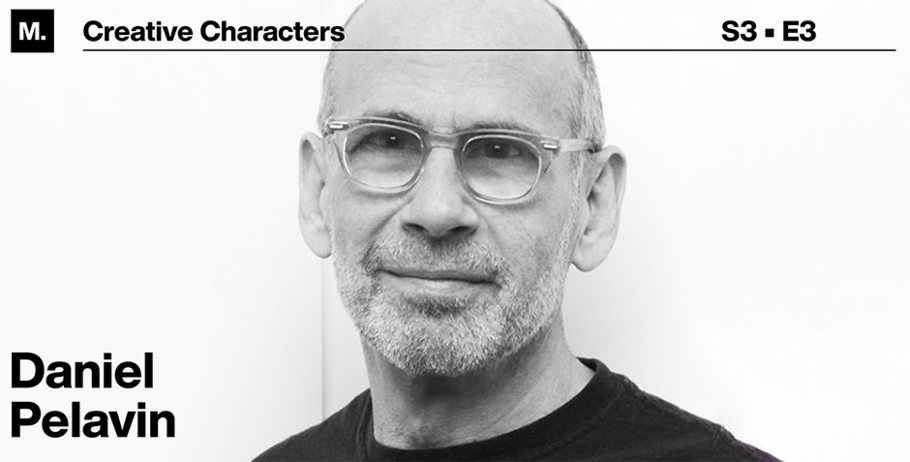

Inside the Studio: Creative Characters — Pelavin Fonts

Chat with illustrator/typographer Danny Pelavin, and you’ll discover that he’s grateful for having creatively come of age in the 1970s, during the halcyon days of design studios in Detroit; that he still does all his lettering by hand; and that he’s not shy about sharing his truths.

A habitué of the phrase “I have to be honest with you,” he admits that procrastination is part of his work process and confesses to fears of being a fraud. Yet he’s enjoyed many successes. Since moving to Manhattan in 1979, he’s regularly contributed drawings to The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Fortune, and others.

In a recent interview with Monotype, he reflected on his professional journey, changes to his industry, and possibilities for the future.

MyFonts (MF): You got your start in Detroit, where you were born. When did you first realize that visual details — drawings — have meaning and importance?

Daniel Pelavin (DP): I was 4 or 5 — hanging out with my Aunt Rose, who was giving my mother a break — and she went to the bank and filled out a deposit slip. Her writing on paper piqued my curiosity around people using letterforms to communicate. It wasn’t just the typography; it was the marks being made by hand. That’s important to me because no lettering comes without a hand being behind it.

MF: When did you start down the path to becoming an artist?

DP: Fourth grade. Due to my [ADD-fueled] behavior, my school suggested that I visit the Oakland County Child Guidance Center. There, they handed me puzzles where you’d predict the next shape. But I’m a big fan of how shapes fit together and what meaning comes from their composition.

Later, I was assigned to industrial drawing classes, because, I believe, they were taught by former Marines. I had my triangle, my French curve, my drafting brush, and I spent my time trying to make shapes as perfect as I could. All these things were a very big influence.

Bigger, however, were my 3.5 years of studio apprenticeships after college. Once hired, I’d enter rooms full of working artists and bombard them with questions till they kicked me out. That’s really where I learned to become an artist — not at a university.

MF: Interestingly, you yourself later served as a college professor, including at FIT, Syracuse Univ., and now, at the Univ. at Hartford?

DP: Yes. I currently teach in one limited-residency MFA in Illustration program. Which is amusing, teaching people to do illustration in 2023, since current industry trends don’t use that skill. But what I teach is very specific. I don’t show people how to do stuff. I encourage them to love what they need to do, knowing that’ll drive them to the effort to accomplish things.

MF: Tell me about your own design or artwork.

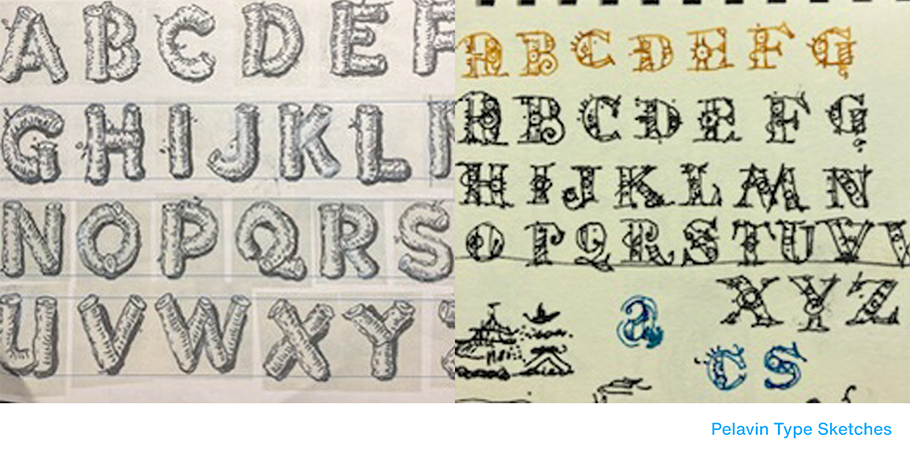

DP: I can talk about Salty Dog. It’s my redo of a classic letterform, used for centuries, that makes lettering out of rope. Salty Dog refers to sailors tying knots, but it also works for Western people making lariats.

MF: What’s your creative process?

DP: When I get an assignment, I begin by procrastinating. I seek out reference words for images that I sometimes print on mood boards. People think, “Great, now you’ve got this sheet that will guide you in your process.” And I say, “No, now you tear up the sheet and throw it away.” Because searching fills your head with what you need to do the job.

Then I procrastinate more. I check my calendar for the latest date I can finish. Then I open this Aquabee Super Deluxe Sketchbook that I love. I draw with a fountain pen. Whiteout’s my command Z; the only way to “undo” ink is by covering it up. I make dozens of rough sketches that I think represent what the client’s looking for. After they choose one, I try to keep them from sabotaging their own job by doubting themselves. Clients who doubt themselves, doubt you.

MF: What’s the work you’re proudest of?

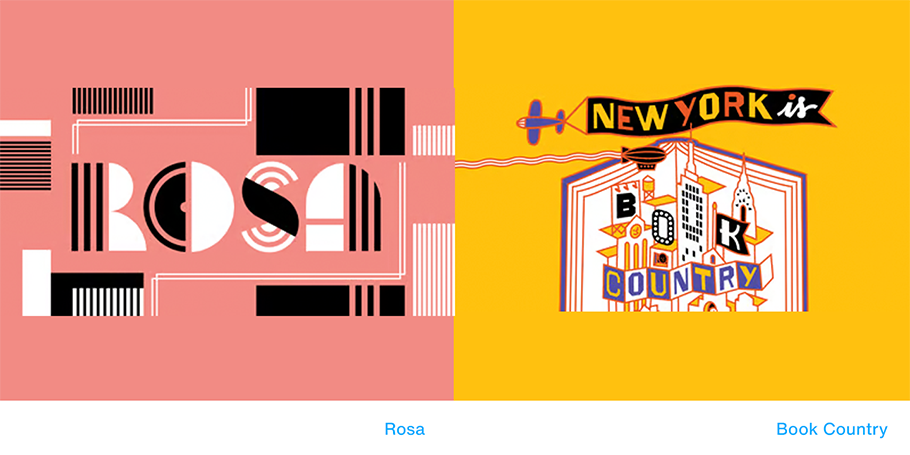

DP: That’s so hard. My website, DanielPelavin.com, includes more than a few projects that I’m very proud of. But there’s considerably more than a few that I weep over and am ashamed of.

MF: What drives that feeling?

DP: After your last job comes that nauseating feeling of you’ve gotten this far with absolutely no talent. That strikes every artist I’ve ever known — even the best, the most celebrated.

I show my work so that people know what I’m capable of doing — that I might be able to fulfill a requirement they have. But in terms of saying, “I’m so great,” it doesn’t happen. When it DOES happen, that’s a clue that you’re not working with an artist.

MF: What do you envision for your future?

DP: I’m in a financial position where I don’t have to work. But I want to, and I’m trying to figure out whether there are reps I need to talk to, or agencies now that hand-drawing is passé. I’m not going ask for classy illustrating jobs because no one wants them done. But there’s certainly stuff that I can do, that I have the skills and the ability in Adobe Illustrator to create. I just like making things.

Give a shout-out on social media using #CreativeCharacters

We hope you enjoyed this interview. Check out previous interviews of Up and Coming Creative Characters & Inside the Studio: Creative Characters.