Alphabet Tree - The Letters I and J

The letters I and J follow each other in the alphabet – and look a lot alike. So, it should come as no surprise to discover that our ninth and tenth letters started out as the same character.

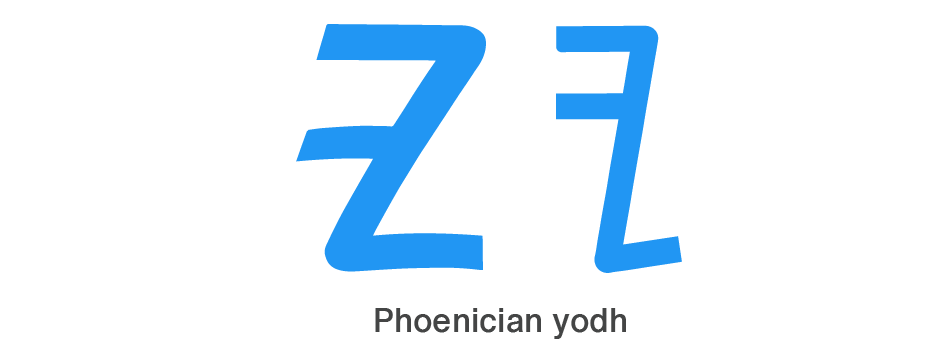

The Phoenician ancestor to our present I was a sign called “yodh,” meaning “hand.” This can be traced back to the Egyptian Hieroglyph representing an arm and hand.

The original Phoenician symbol evolved over time into a zigzag shape that was eventually adopted by the Greeks. The Greeks often simplified the symbols they borrowed, and the yodh was no exception. As used by the Greeks, the zigzag eventually became a simple vertical line. The Greeks also changed the name of the letter to “iota.”

Iota was the smallest letter of the Greek alphabet and, as such, has come to mean “a very small amount.” The word “jot” also derives (via Latin) from the Greek iota, and usually refers to a small note or mark.

Like the G and F, the letter I took its time deciding which sound it represented. The Phoenicians used it as a semivowel, as the ‘y’ in toy. When the I was adopted by the Greeks around 900 B.C., they used the letter to represent the long ‘ee’ vowel sound. Then, in early Latin, the I represented both the vowel ‘i’ and the semivowel ‘y.

Both I and J were used interchangeably by scribes to express the sound of both the vowel and the consonant. It wasn’t until 1524 when Gian Giorgio Trissino, an Italian Renaissance grammarian known as the father of the letter J, made a clear distinction between the two sounds.

About Those Dots

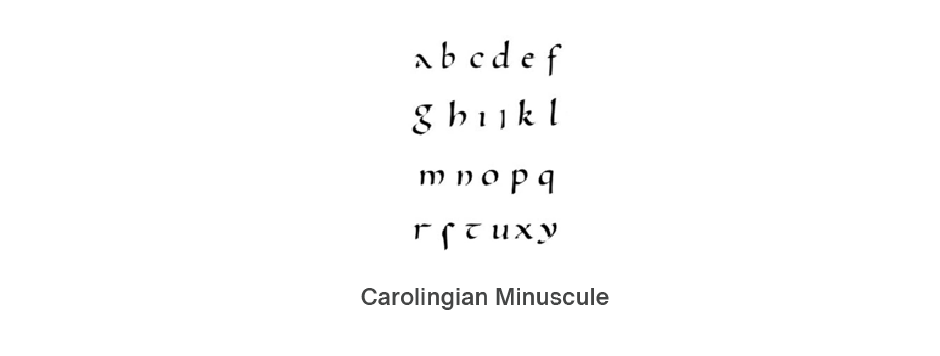

The Carolingian Minuscules, forerunner of our lowercase alphabet, was used for all legal and literary works to unify communication between the various regions of the expanding European empire. Originally, the i and j did not have dots.

The dot, or tittle, first appears in manuscripts of about the 11th century and was used to distinguish the letter and assist reading in words in which it was in close proximity to letters such as n or m (like in the word “mimic”). The dot frequently took the form of a dash. It became the custom in medieval manuscripts to distinguish an initial or otherwise prominent I by continuing it below the line, and it was from this habit that the differentiation of the letters i and j arose. The two letters were not considered as separate until the 17th century

As a result of legibility and readability studies of textual copy, the Mergenthaler Linotype Company designed several new typefaces in the 1920s and 1930s. Ionic N°5 was the first. Chauncey H. Griffith, who eventually became Vice President of Typographic Development, was responsible for the design.

Drawn specifically for periodicals of the time, Ionic N°5 was quickly adopted by newspaper publishers around the world. In less than 18 months, it was used by nearly 3000 newspapers. Based on this success, Ionic N°5 was followed by four additional families (Textype, Excelsior, Paragon and Opticon). These typefaces became known as the “legibility group,” and were widely used well into the 20th century.

Almost a hundred years after Ionic N°5’s first release, Clément Charbonier Bouet and Malou Verlomme, of Monotype, set out to revive the typeface. The result is a contemporary interpretation of the original goals, tailored for print and digital designers of the 21st century.