Discover legacy content from FontShop.com, preserved for your reference.

Trend revived: Sausage type

When the Volkswagen Corporation was in need of a new corporate identity in the 1970s, they commissioned Wolf Rogosky and Gerd Hiepler to design a custom typeface for them, which would supersede Futura and be implemented in all VW applications including its subsidiaries (e.g. Audi). The type to be known as VAG Rundschrift – the one typeface that cannot be left out in any contribution about the rounded style – was finished in 1978 and provided the car manufacturer with a friendly and fresh look. Even though VAG Rundschrift is no round Futura, several characters are reminiscent of the geometric sans from the 1920s; most notably the one-story ‘a’, the lowercases ‘j’ and ‘t’ without arcs, the ‘u’ with no down stroke and the famous numeral ‘1’. Overall the capital letters have different proportions, however.

[link not found]

Some years later Bertel Schmitt and Manfred Schwarzer reworked VAG Rundschrift and it was redesigned again by David Bristow and Gerry Barney, who had also worked on the Volkswagen corporate design. When the typeface came into public domain in the late 1980s it was available from Berthold as a headline font first. Today it is released with a number of different foundries; extended to a series of four weights (thin, light, bold and black), improved for optical size 18 pt and made available as VAG Rounded, praised “for technical and instructional manuals, or advertising.” During the era of such typefaces, typographers have coined the lovely term „Würstchenschrift“ (sausage type), hinting towards letterforms that look much like sausages (capital letter ‘C’ in particular), at the same time it was Volkswagen’s custom type that made this style acceptable for larger corporations. What’s more, VAG Rundschrift anticipated the revived trend of rounded typefaces in the 1980s.

This trend mainly focused on the rounding of existing faces, static sans serifs in particular. Linotype began with issuing Helvetica Rounded in 1980, followed by AG Book Rounded, designed by Günter Gerhard Lange and released with Berthold in 1984 (‘AG’ is short for Akzidenz Grotesk). It took almost ten years until Monotype’s type department responded with their rounded version of Arial. Robin Nicholas, who designed Arial in collaboration with Patricia Saunders back in 1982, also drew MT Arial Rounded. The causal relationship of Akzidenz Grotesk, Helvetica and Arial and their resemblances based on this connection are increased in the result of the rounded letterforms, though ‘a’, ‘G’ and ‘R’ remain visual aids. All three faces are popular round solutions that are frequently used in print media and in public space, but no other rounded typeface from this era is as successful as VAG Rounded. It was influential for other types of the rounded style and even after it was taken out of service at Volkswagen it found new followers; one of its most infamous applications is its use on the Apple Keyboard introduced in 2007 (superseding Univers condensed oblique) – which became a very appropriate solution for the black back-lit keys on the unibody line of the MacBook Pro series. The next chapter explains why this is appropriate.

Technology: Signs and screens

Typographers deal with readability and legibility problems; several parameters such as line spacing, character spacing or tracking can be adjusted to improve text in captions, headlines on posters, or instructions to be read from far away. But there are exceptional challenges where typography hits a glass ceiling and changes to the typeface itself need to be made. When a signage system is backlit, type will be outshone; even the sharpest edges will blur and appear out of focus. So if type is sharp in one application, but the same type appears round in another environment, we are losing control and thus have a problem, as both cases may not be recognized as one brand. The solution to this problem is a typeface that is equipped with round shapes and corners in the first place. In the end the result is honest: what you see is what you get.

When Dutch creative director Pieter Brattinger assembled a team to create the Amsterdam metro signage in the early 1970s, Gerard Unger joined in as their type designer. From the beginning, it was clear that a fair share of the signs would be backlit and so Unger equipped them with a corresponding typeface. By 1974 he finished M.O.L. (Dutch for mole, the metro’s new mascot1]), a typeface that features wide-open counters and overall round letterforms to improve legibility.

M.O.L. was only Unger’s second professional typeface, but with the experience of his first, Markeur, designed in 1972, he was already familiar with challenges associated with the rounded style. He developed Markeur explicitly for signage purposes (i.e. for hospitals, authorities, etc.) as a young employee at the Enschedé type foundry on the Pantotype, a pantographic system to engrave letters for signs. In the master drawings for the engravings Unger purposely widened the stroke endings to prevent the machine from cutting them too round. Dutch design critic Jan Middendorp detects Unger’s approach in the design of Markeur as a response “to the given technical constraints by designing a letterform that solves the problem in a very practical way.”2 And Unger did so in designing M.O.L. as well.

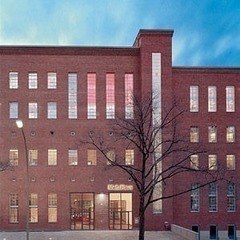

Over twenty years later, MetaDesign Berlin was confronted with the same challenge for the Düsseldorf Airport signage system, but with a more nerve-racking background story. In the spring of 1996 a fire broke out at the airport, killing 17 people who died due to smoke inhalation rather than the fire itself. The Berlin-based design office was commissioned to develop a new signage system within only six weeks, without a real test phase, during the main holiday season and in-between temporary tents and construction. Luckily Erik Spiekermann, who led the design team, pulled a typeface out of the famous hat: eight years earlier he had designed Fidia for an Italian pharmaceutics company of the same name that featured slightly round corners to appear warm and appealing on small packaging3. It was never realized, but the design came in handy for the Düsseldorf Airport signage, which was completely backlit. Within four weeks of further improving and adjusting letters, Spiekermann, with the help of Albert Pinggera and Ole Schäfer, created the typeface known as FF Info Display, to be applied in white on opal green backgrounds. The corners of FF Info Display are slightly rounded, just enough to avoid halos and also perfect to enable quick cutting of roughly 2,500 signs on the plotter. Typical of Spiekermann’s faces, it appears more narrow than its competitors, it is equipped with a serif on the ‘i’, two serifs on the ‘I’ and a hook on the ‘l’. In the end it takes up 12% less space than i.e. Helvetica or Univers.4

[link not found]

A decisive feature is the introduction of different weights; when type is applied on a dark backlit background, it should not be too bold, because the shine makes it appear even bolder. Shapes will be more legible, when a thinner weight is installed instead. Therefore FF Info Display’s regular weight is the solution for a “negative” (i.e. white on black) use of type, while medium works for “positive” (black on white). Spiekermann had already developed an entire series of such weights for his signage-improved version of Frutiger that goes by the name FF Transit for the Berlin Transport Authorities (BVG) in 1990. With Lucas de Groot he developed a system that considered differences in front- or backlit and whether the type is white on a dark background or vice versa (but without round corners): Transit Front Negative, Transit Front Positive, Transit Back Negative, Transit Back Positive.

Screens are tricky media for type, too. There are many manufacturers and several different resolutions. In the 1970s screen resolutions were particularly low, which resulted in type appearing fuzzy and round. Again, the solution was to design it round in the first place and avoid unpleasant surprises. Only one year before the Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen (abr. ZDF, Engl. Second German Television) went on air with their newly renovated studio and TV program, the channel commissioned German designer Otl Aicher to redefine their corporate identity in fall 1972, “to present them in the right style” and to design “a binding typeface with tube-like instead of square letters.”5

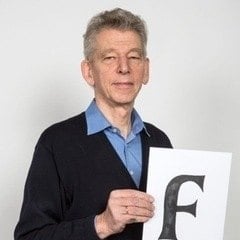

Similarly, East German designer Axel Bertram developed a custom typeface for the two television channels of the German Democratic Republic between 1983 and 1986. He had already made a first proposal to rework the channels’ corporate identity along with a typeface to be used on screen in 1979, but it took quite some time until he was officially commissioned. From his research on conflicts and conditions of a 625 line screen resolution, Bertram deduced: 1. Letterforms of a serif face are recognized more easily than those of a monolinear sans; 2. Compactly shaped serifs stabilize letterforms and improve readability; 3. An alternating stroke contrast enhances legibility.6

Bertram operated the type generator Chyron to create image lines as well as colorful knot-like clouds for serifs. This apparatus was in use by the channel during the day, so he could only work on it at night.7 While Aicher revised an existing sans serif type for different circumstances, it was Bertram who developed a new roman face from scratch and therefore explored best possible solution for serifs on screen. Ultimately, the concentration of stacked pixels in one spot seemed to be a convincing solution to make serifs visible in spite of low resolution. In 1986 Bertram finished three weights of Videtur, Latin for “it will be seen”. While the type was never entirely used by the channels and did not get full recognition, it was digitized years later in collaboration with Andreas Frohloff and released as FF Videtur on FontShop in 2012.

To be continued … part 3 of this article will further take on exclusive round typefaces of smaller companies and large corporations.

Bibliography and further reading

Koeberlin, Christoph/Dan Reynolds: Socialist TV typeface Videtur finally freed, on: ilovetypography.com [last opened 4.2015]

Monotype GmbH (ed.): Rounded fonts are back in vogue. An historical and current overview, published on linotype.com, 2014 [last opened 4.2015]

References

1. Gerard Unger describes the naming of the typeface on his website gerardunger.com/allmytypedesigns [last opened 04.2015]

2. Middendorp, Jan: The pragmatism of Gerard Unger, in: Dutch type, Rotterdam 2004, p. 167

3. From correspondence between Spiekermann and the author, 9 February 2015

4. Erler, Johannes: Hello I am Erik. Erik Spiekermann: typographer, designer, entrepreneur, Berlin 2014, p. 191

5. Der Spiegel, no. 33, Hamburg 1973, p. 91

6. Koeberlin, Christoph/Dan Reynolds: Socialist TV typeface Videtur finally freed, on: ilovetypography.com [last opened 4.2015]

7. Bertram, Mathias: Axel Bertram. Grafisches Gestalten in fünf Jahrzehnten, Leipzig 2012, p. 172