Discover legacy content from FontShop.com, preserved for your reference.

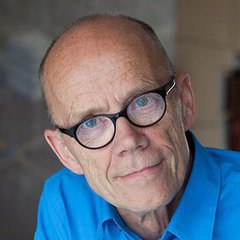

There are different concepts of such visual systems in type design. This can be anything from a series of widths to a typeface with a spectrum of more than two or four weights (regular, bold and respective italics used to be common) to establishing parameters which allow for an interrelated combination of different styles (mixing sans with serif or with slab or any other hybrid version of these). In an article like this one, there is of course no escape from Univers. Many agree that this face designed by Adrian Frutiger and released by Deberny & Peignot in 1957 was the first to appear on the market as a coherent system and it was in fact planned as such at the beginning of the design process. According to Erik Spiekermann it was Adrian Frutiger who first followed the principle that type design is placed in the “context of planning rather than following an artistic stimulus” in exemplary manner and that it was he who first saw a type family as a closed system in which several weights are combined without “aesthetic compromises.” 2

[link not found] So while Univers was the first of its kind in terms of its concept, its consistency and certainly in terms of its dimensions, there had also been several type designs with a systemic approach long before that. At the same time Adrian Frutiger paved the way for so-called type families, well built in weight, width and style. When ITC Officina, FF Scala and Thesis were released over twenty years ago – all of them are classics today – this practice still was not nearly as common as today. In recent years we have seen many more type families than ever before, always trying to further exhaust the rules of letterforms in extreme dimensions and the ones that stand out are those that set new standards.

Wooden widths

In his extensive book on American Wood Type: 1828–1900, Notes on the Evolution of Decorated and Large Types (New York, 1977) author Rob Roy Kelly (1925–2004) explains: “The condensing and expanding of type designs has been attributed to Americans more than to Europeans, and there is evidence that many of these variations sprang from the wood type producers.” 3 Kelly’s evidence are several early examples of wood typefaces cut in series of six to eight widths. The industrial production of wood type had its heyday in the mid and late 19th century (before posters began to be printed lithographically), but large amounts were manufactured nevertheless until the 1960s. 4 In American Wood Type three groups of typical plain typefaces, so-called “primary faces” are listed: Roman, Antique (nowadays commonly known as slab serif) and Gothic (sans serif). Wood type producers were always concerned with further expansion of their repertoire.

Obviously the production of wood type was different from that of metal type in terms of flexibility and speed; in wood type different sizes could simply be defined by the customer’s choice and variations of a design were marketed much more quickly. Such variations were of course italics, but also ornamented, perspective, outlines, double outlines, open shaded, line shaded, ray shaded etc. In the 1840s condensing and expanding the width or changing weights in a single design became a common practice. This was also due to a device known as pantograph, based on the scissor mechanism with multiple axes. With a pantograph the movement of a tool (i.e. tracing an image) could be repeated in another movement. Most commonly used to scale drawings, engravings and milling cuts up or down, existing patterns could also be compressed or extended by moving only one axis without moving the other.

According to Kelly, the wood type manufacturers developed an interrelated system of widths by 1880 comprised of condensed, extra condensed, double extra condensed, treble extra condensed etc. as well as extended and expanded. 5 In type specimens every “extra” in their names was abbreviated with an ‘X’. Kelly claims “this system was never used as consistently or to the same degree by the typefounders as it was by wood type producers.” 6 Another difference was the employment of the “parent letterform” in the naming of a wood typeface (Antique Tuscan XX Condensed), while type founders often assigned an “unrelated name to each style of the same design.” An interesting detail is the increasing or decreasing of the strokes with each expansion or reduction of the width, i.e. a condensed regular letter became light when it turned into an extra condensed or bold when transformed into an extended.

Wobbly weights

In Germany the wood type tradition is not nearly as significant as in the United States and also advertising developed more slowly. With the end of the first decade of the 20th century, however, came a change in lithographic poster design. Art Nouveau and Historism were slowly counted out, after almost every small announcement had looked like a membership invitation to the Knights of the Round Table. This aesthetic was no longer suitable with developments in industry, technology and trade – with new necessities came new form.

[link not found]

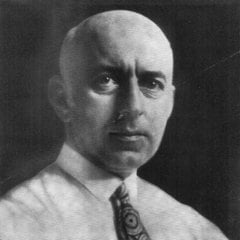

Typefaces with rough contours that looked spontaneous and as if they were hand-painted soon became popular for everyday printing, known as jobbing, and later in advertising. This characteristic was ideal for jobbing, as bad adjustment on the printing machine did not become apparent in the final prints so easily. A pre-eminent figure in poster design at that time was Lucian Bernhard (1883–1973, known as Emil Kahn until 1905), whose trademark was painted wobbly bold type. With Bernhard Antiqua he managed to transfer this aesthetic to metal type for printing in 1911 for the Flinsch Type Foundry and one year later for Bauer. A bold italic and Bernhard Fraktur (blackletter) followed in the same style, creating a little series that carried his name.

Bernhard may have influenced one of his contemporaries, Hermann Hoffmann (1856–1926), who worked for the Berthold Type Foundry at the time. 7 Hoffmann took the idea of a wobbly advertising type to the next step and created a whole series ranging from light to heavy along with condensed and compressed weights called Block in 1908. What’s more, with the help of numerous alternative letters and ligatures the perfectly justified “block” of text could be created. Lines ended up longer or shorter by simply exchanging single letters with their narrower or wider alternatives – without disturbing readability. The playful Graublock (cut in thin lines with slim intervals that created a grey shade instead of black when printed), Hochblock with extreme ascenders and Block Fraktur complete the Block family of different weights, widths and styles.

Block’s light weight is also listed as Berliner Grotesk in some of the older type specimens. There is evidence that it was originally designed by Louis Oppenheim (1879–1936), 8 the father of Lo-Type, another typeface with rough contours in a few weights and widths. In 1978 Erik Spiekermann brought Block light condensed and medium together to form the Berliner Grotesk mini series for Berthold’s phototype program and two years later he also redrew Lo-Type for the new technology.

Mixed styles

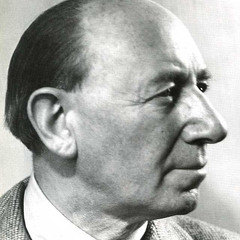

The fact that both Bernhard and Hoffmann applied the wobbly characteristic of their typefaces to respective blackletter styles is noteworthy, for the equal use of both roman and blackletter was a unique characteristic to the German speaking countries at the time. Books were printed in both styles and sometimes one was used to stress words in a body of text set in the other. But it was Jan van Krimpen (1892–1958) who first made a brave attempt in bringing serif and sans serif together in one family in the 1930s. Shortly before him, Eric Gill (1882–1940) designed Gill Sans in 1926 (released with Monotype two years later) and Joanna in 1931 (Monotype, 1937). Both typefaces bear an extremely harmonious family resemblance that allows them to complement each other on the printed page. The Dutch type designer Martin Majoor has suggested: “While [Gill] may not have realized it, he based his Gill Sans on the typefaces in his head. […] Had Eric Gill planned Joanna and Gill Sans as one family he would have been the first in history to design a family of serif and sans.” 9 And so instead van Krimpen did.

After few years of designing, the Enschedé Type Foundry began to release van Krimpen’s Romulus Roman in 1932. A chancery-like swashed version known as Cancelleresca Bastarda came out in 1937. A year earlier Romulus also hit the market with Monotype. Semi-bold and semi-bold condensed weights followed and the regular was available in Greek letters as well. The really remarkable addition to the Romulus family was a sans design to augment the serif. Light, regular and semi-bold weights were in planning for this style, but van Krimpen never made it past the experimental stage.

, designed in the [Type and Media](http://typemedia2012.com) Masters course at the [Royal Academy of Art](http://www.kabk.nl/), The Hague in 2012.](https://lg-assets.myfonts.com/fs/uploads/content_image/attachment/101409/mini_magick20141021-16370-wkn42f.jpg)

Well-planned sizes

A peculiarity of metal type that has not yet been mentioned is the range of type sizes cut for each design. The concept of having optically adjusted versions for each size had been a constant systemic companion of metal type since its early days. Metal typefaces would commonly range from 6 point (but also lower) to 72 (and higher) in a rigorous system of given sizes, which were all designed and cut separately with much attention to the respective contrast of thick and thin strokes or to the optical size of counter forms. Almost all countries in Europe agreed to measure their type sizes in the French Didot-point system (0,3759715 mm) and many of the sizes have French names such as Nonpareille (6 pt), Petit (8 pt) or Bourgeois (9 pt). Another unit within this well-planned system is a cicero, which equals 12 point. Thus larger point sizes beginning with 36 pt (3 cic) came in intervals of 1 cicero (48, 60, 72, 84, 96), although sizes between these were also available.

A 1925 specimen of the not so well-known German type foundry Schriftguß AG (originally Brüder Butter) in Dresden reveals an interestingly well-built typeface series called Grotesk Serie. While it looks like many of the popular static grotesque types of the time (Annonce, Anzeigen-Grotesk, Aurora) at first glance, it has a few features such as the Art-Deco-like bows in ‘A’, ‘M’, ‘V’ and ‘W’ that distinguish it from its contemporaries. This grotesque family is comprised of 10 weights ranging from light to condensed extra bold. Some weights are available from 6 to 36 or 48 pt, others go up to 72 pt, culminating in a total of 132 sizes in the complete family. Starting with the light weight, nicknamed Planeta in the specimen, the following six weights are named after planets: Saturn, Jupiter, Neptun, Uranus, Merkur and Mars. The final three weights are also listed as Reklame-Grotesk (Reklame meaning advertising) with nicknames Sirius, Orion and Pallas, available in up to 96 pt – truly a system by its number of weights and by its naming.

letterpress shop in Berlin.](https://lg-assets.myfonts.com/fs/uploads/content_image/attachment/101326/mini_magick20141021-16370-mt01gk.jpg)

Related by marriage

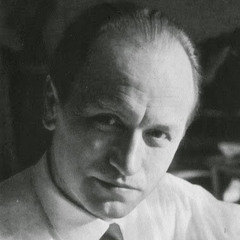

An interesting example for a system of typefaces with an organizing principle based on different sizes to create visual hierarchy is the family of designs surrounding the famous Palatino. Until today it is perhaps the typeface that Hermann Zapf is best known for. Originally its working title was Medici Antiqua and it was mainly intended for display use. Nevertheless Palatino was first used in several publications as a text face (namely in Zapf’s Pen and Graver, New York 1952). By 1950, the year of its release with the Stempel Type Foundry and Linotype, Zapf noted “the Palatino face was destined for extension into a type family.” 10 The following year Palatino italic was released for the Linotype with a width matching that of its roman, while Stempel issued a slightly narrower version of its own for foundry type.

After his return from a trip to Italy Zapf was inspired to draw two titling faces to accompany Palatino: Michelangelo (1950), a set of light capitals and Sistina (1951), also caps, but narrow and much bolder. For explicit use in large formats in type sizes up to 20 cic Sistina Plakatschrift was produced in wood (1953). With three family members intended for display use, it was time to finally extend the family to Aldus Buchschrift, a real book face, from 1952 to 1954. Produced only in 6 to 12 pt with matching italics and small caps, Aldus is rather slim and slightly more delicate than its older sister. Greek language extensions followed as Phidias (1953), to be used in combination with Michelangelo and as Heraklit (1954), designed to match Palatino. In the overall concept of a system of related typefaces Zapf made sure to develop “a most careful gradation of scale” in all of the sizes’ weights. 11 Thus, a balanced ratio of cap height to stroke thickness was developed in each typeface: Michelangelo 1:12, Aldus 1:11, Palatino 1:9, Sistina 1:7, Palatino bold 1:5.

A Stempel type specimen published in 1953 titled Eine Familie stellt sich vor (A family introduces itself) does not only list all of the family members above, but also suggests that other typefaces by Zapf are related by marriage. The specimen reads: “Not to forget the strong brother-in-law Kompakt” and “at last the blackletter type Gilgengart shall not be forgotten. […] Next to some type of the Palatino family […] one would like to recognize it as a relative.” Of course these passages should be read with a wink of the eye – a nice marketing gag by Stempel nevertheless.

In another 1953 specimen Palatino: Eine verzweigte Familie mit der Sie immer zusammenarbeiten sollten (A large, extended family you should always work with) Palatino medium, small caps and swash characters are listed as part of the family. Zapf-expert Jerry Kelly has suggested that the Palatino family was “the largest type family based on classic renaissance forms.” 12 Even though the Palatino family appears to be a system of assembled individual typefaces, each with a different name, they were meant to orchestrate in a harmonious visual hierarchy. With the re-release of Palatino as Palatino nova, Michelangelo was named Titling and Sistina became Imperial, however, these titling faces seem to be forgotten just as much as Aldus, which can rarely be found in books from the Inselbücherei series.

Impeccable system

When the French Deberny & Peignot Type Foundry set up a new type program for the Lumitype photo-typesetting machine (later for Photon) in the early 1950s, Futura (known in France as Europe) was to be included at the wish of director Charles Peignot, but Adrian Frutiger proposed the concept of a new sans serif to be selected instead. In his view Futura no longer represented the spirit of the time and he argued, “a purely geometric type [would] not be tenable in the long run.” 13 Frutiger wanted to design a universal typeface; one that could be used for a variety of applications and that would suit the demands of typography in those days; simple, functional, reduced to the essentials. Most importantly he had a large family of styles and weights in mind. From the beginning on he drew characters for each of the weights and the brave idea was to release them all at once, before even testing the popularity of a single weight in advance. 14

The Univers family is constructed on a coordinate system, letters transform on either the weight axis or the width axis – or both. It ranges from thin to black on the one side and from condensed to extended on the other with upright and oblique forms in between. Gradual increase or decrease result in a change of inner space (both open and closed counters) and side bearings.

One of Frutiger’s central themes in the design process was consistency. Other sans serif typefaces at the time were also well-built, such as the geometric Futura or the static Akzidenz Grotesk (which also included condensed and expanded weights), but especially these faces revealed discrepancies in the spectrum of weights: in the transition from Futura’s medium weight to bold some letterforms such as the ‘e’ suddenly turn from open to closed, in Akzidenz Grotesk (also simply known as “AG”) a change of letterforms occurs from light and regular to medium (especially in the regular weight Serie 57 – released in 1962) and within the different widths. However, it should be pointed out that AG’s inconsistency is rooted in its long history of weights designed by different designers (paternity remains unsolved) and that it ended up as an interrelated family much after its first release by Berthold in 1898.

In Univers on the other hand all terminals end horizontally throughout the weights and widths. Frutiger even later admitted: “I was aware that in the regular weight a diagonal, classic curved end would have been nicer, but I wanted to make 21 weights and I couldn’t cut the narrow weights diagonally, it just didn’t look good. […] The horizontal ending was a matter of consistency for me, with respect to the whole family.« The exceptions in the lowercase ‘t’ and in the question mark (only in the expanded and normal weights) prove the rule.

Univers was planned in 21 weights from the beginning. Therefore a two-digit numbering system was introduced to distinguish the different styles within the system early on. The first digit describes the stroke width (ranging from thin to black) while the second digit stands for width and slope (ranging from ultra condensed to extended and alternating between upright and oblique) in which odd digits mean upright and even digits mean oblique. Numeral 5 covers the “normal” case and as such 55 stands for regular weight upright. 56 describes the oblique counterpart. 57 is roman condensed upright and 65 is medium upright and so on.

Early on in the design process Frutiger used a diagram to illustrate his system of weights and widths – first without and later with the according numbers as a guideline. In small frames to border on one another the letters ‘H’, ‘E’ and the word monde (French for world, one of Univers’ initial working titles – as opposed to Europe) were typeset in each of the parameters. In the year of Univers’ release a revised and much advanced version of this diagram was first published in the Swiss graphic design journal Typographische Monatsblätter no. 5. Shortly after it was Rémy Peignot (1924–1986), Charles Peignot’s son and in-house designer at Deberny & Peignot, who created a predecessor of a version of the diagram that is so well known today and that has been reproduced multiple times. Instead of monde, each of the boxes reads the word univers.

In 1964 Rémy Peignot designed a notable letterpress printed booklet of loose specimen sheets. The diagram appears in color (to distinguish the respective styles even more successfully) on the first page while an almost pictogram-like miniature version of it is used on each of the pages to locate that weight within the system.

in 1964 is one of the most notable type catalogues ever published. It opens with Peignot’s Univers diagram, that is used in a miniature version for navigation on the collection of loose sheets to indicate each weight’s position within the system. (Reproduced from *The Book of Books*, Cologne 2012, with kind permission of Mathieu Lommen)](https://lg-assets.myfonts.com/fs/uploads/content_image/attachment/101345/mini_magick20141021-16370-npmy6x.jpg)

The cover reveals the pattern of another simplified Univers-diagram, designed by Frutiger’s assistant Bruno Pfäffli in 1964 and first published in a Monotype Newsletter a year later. It simply displays the lowercase letter ‘u’ in each of the weights and its respective obliques.

In a Univers specimen issued by the American Type Founders, ATF, Peignot’s diagram is also used on the cover, added with page numbers at each weight to serve as a table of content. Not only does Rémy Peignot’s Univers booklet remain to be one of the most beautiful type specimens ever designed, but foremost he and Pfäffli found comprehensive and simple ways to translate the complex visual system that underlies the Univers concept.

Super families

The transition to the digital age enabled completely new possibilities in type design. These changes were in favor of large families with multiple weights. One of these earliest designs was Erik Spiekermann’s Officina (orig. Correspondence) for the International Typeface Corporation, released in 1989. Spiekermann’s original intention was to design a contemporary correspondence type consisting of a sans inspired by Letter Gothic and a serif borrowing ideas from Courier brought together to shape a unified pair. After a while the idea for the serif was given up though and eventually, with the help of Just van Rossum, a slab serif was derived from the sans. 15 Both styles came in multiple weights from book to black, making it one of the most popular fonts from ITC. In 2003 a display version followed that included a light weight as well as arrows, bullets and circles.

Sans and serif typefaces that derive from the same designer and thus share a certain heritage go together well most of the time, as has been said about Eric Gill’s Gill Sans and Joanna. A case that proves this observation in exemplary manner is the combination of two type families by Spiekermann surrounding FF Meta and FF Unit. Originally planned as an exclusive type for the German postal service Deutsche Post in 1984, Meta (then known as PT55) was rejected by the client and subsequently became one of the first typefaces to be released under the FontFont label in 1991. FF Meta grew to a fairly large family of different weights in the 1990s and then in 2002 FF Unit was released, a somewhat grown-up Meta with less playful terminals of the strokes. With the releases of FF Meta Serif in 2007 and with FF Unit Slab in 2009 both Meta and Unit were equipped with serif counterparts. It is important to point out, that while FF Unit Slab is based on FF Unit, FF Meta Serif is not a “serifed” FF Meta.

Just like ITC Officina, all of the typefaces share the signature of its designer. As a consequence they complement each other in several possible combinations. Shortly after the release of FF Unit Slab, FontFont explained on their website: “FF Unit Slab […] can be mixed with FF Unit, of course, but also works as companion to FF Meta, while FF Meta Serif looks good when mixed with FF Unit.” Christian Schwartz, the type designer who assisted Spiekermann on Meta Serif and ‘the two Units’, explained the family relationships in slightly different vocabulary: “While FF Unit is FF Meta’s ‘grown up sister’, FF Unit Slab and FF Meta Serif are more like second cousins.”

[link not found]Somewhat true to the humanist serif faces of the 15th century, but with less contrast and equipped with stronger, almost slab serifs, Martin Majoor began designing his typeface FF Scala in 1987, for a music centre in Utrecht, Netherlands, before it was released with FontFont. Similar to Frutiger, who had learned to develop sans serifs modeled on roman types early on in his studies in Zurich, 16 Majoor explains how FF Scala Sans literally came to be by superimposing it on the serif original and using simple tools such as marker and correction fluid. This resulted in a common “skeleton”, Majoor’s philosophy: “two typefaces, one form principle.” Scala had already hit the market in 1990, but it took another three years for it to become a success with the additional release of its sans serif counterpart. More extreme weights followed in 1997 as well as the display version FF Scala Jewel.

specimen by [Evert Bloemsma](/designers/evert-bloemsma) were produced on the same print sheet, thus both feature the same coloring.](https://lg-assets.myfonts.com/fs/uploads/content_image/attachment/101370/mini_magick20141021-16370-1gzoo59.jpg)

[link not found]

A type designer who has had a huge impact on the idea of type families is Lucas de Groot with his hit Thesis and a theory for calculating intermediate weights. Released with FontFont in 1994, Thesis has expanded to a super family in the following years that now consists of The Serif, The Sans and a semi-serif hybrid called The Mix. Each family consists of 16 weights (italics included) and The Sans and The Mix are additionally available in the same set of weights as Mono (monospaced) versions. With its 144 styles Thesis was FontFont’s largest family and without rivals in terms of its range of characters for many years.

While Frutiger, Zapf and their contemporaries still had to draw each weight from hand, not to mention the cutting in metal (the complete Univers for foundry type consisted of 35,000 punches), the introduction of computer-based help to calculate and quickly produce intermediate weights has been tremendous relief. Of course there are still type designers who draw each font ‘from hand’ (or rather with a digital pen tool), but the production of large families with the aid of interpolation is certainly acknowledged. Interpolation generates intermediate weights that sit between two basic values, also known as “masters” in technical jargon. Following the computer-based calculation, final corrections nevertheless need to be made by hand, special attention has to be paid to optical behavior.

De Groot has contributed to the concept of interpolation with his own theory. Early on in his career he found that the optically correct stroke thickness lies slightly under the created “average value”: 17 if the ratio between vertical and horizontal strokes in the light master was 1:1 and 3:1 in the bold master, then the ratio in the created intermediate weight lied under the value of 2:1. De Groot’s theory also led to the realization that strokes on the vertical axis must grow more slowly than those on the horizontal axis. Such optical behavior of increasing weights is a challenge that type designers have to take into account. Recently de Groot’s versatile system was extended through an Arabic version in The Sans.

A type designer who has proven more than once that he has a weak spot for large typeface families is self-taught Warsaw-based Łukasz Dziedzic. With FF Clan released in 2006 he joined the club of multi-weights and through this well-built legible typeface in seven weights and six widths he was right at the front. Due to personal experience in editorial design he is in favor of large x-heights and short descenders and knows much about the demands on a useful typeface from the viewpoint of a typographer who would design magazines, books and newspapers, i.e. his typefaces are provided with small caps in each weight. Especially the extreme weights come in handy for display purposes. FF Clan’s dimensions that open up so many possibilities have led to its recognition by large international corporations such as United Airlines where the typeface is in use in the overall visual identity.

But that’s not all: originally released as a rather discreet series of weights in 2007 Dziedzic began a project that has just recently culminated in a system of 196 styles: FF Good. Back in 2010 he had already extended that family from 9 to 30 styles only to rework it to more than six times the amount up until 2014. In a carefully balanced spectrum of weights and widths Dziedzic has once more created an impeccably consequent visual system.

In a recently issued specimen poster by FontFont one can marvel at that spectrum in a beautiful waterfall-like arrangement. It is an overview in tradition with Rémy Peignot’s diagram. Frutiger once made a comment claiming Univers was constructed “like a star” within its diagram. 18 This can in fact be said about the diagram and the concept of FF Good as well; the four masters are sitting in each of the four corners, from compressed light to extended ultra and from extended light und compressed ultra – and vice versa. The four poles are the columns of the typeface and the other 47 upright weights are modeled upon them.

Dziedzic also overcame the hardest part in designing a well-built system of weights that culminate in compressed light on the one end and in extended ultra on the other: consistency in the endings of the strokes and in the proportions of loops and counters. A special case is the lowercase ‘g’ in its double loop appearance. Frutiger had tried to include this shape in his Univers system at first, but ultimately it was rejected, because “it looked forced in narrow, small and italic weights.” 19 Other designers have experienced the same troubles and have thus changed to a two-story ‘g’ or switched to it at a certain weight within the system. Dziedzic was able to retain the shape of the double loop ‘g’, because he made compromises that were planned from the beginning; instead of emphasizing the diagonal strokes, he focused on the horizontal ones.

When we take a closer look at some of the typically tricky stroke endings, for example in ‘a’, ‘e’, ‘f’, ‘r’, ‘s’ or ‘t’, we detect that Dziedzic maintained his course in every one of them and kept his predefined organizing parameters throughout the system. As a result every weight and style can be used in combination, always complementing each other.

The shapes of FF Good are reminiscent of classic American-style gothic typefaces. Just like its ca. 130-year-old gothic predecessors in the wood type era it comes in seven different widths, but in a much-improved manner; while the wood type letters increased in weight at the same time, Dziedzic optically maintains the stroke thickness in each weight.

Since its initial release FF Good has already been used in several editorial publications. A peculiarity of Dziedzic’s typefaces (possibly derived from his experience in editorial design) is the including of a News weight, which sits between regular and medium. It moves in the tradition of the book weight as it has been seen in many classic typefaces and it is ideal for legibility in newspapers. As if 110,000 glyphs weren’t enough, Dziedzic “simply” doubled the amount by developing FF Good Headline to be used in larger type sizes. While FF Good is mastered for text use, its Headline version comes with shorter ascenders and descenders, caps are slightly shortened and overall it is optimized for maximum compactness and display use.

The only question remaining is that of a serif companion. And of course Dziedzic has already given the answer in the shape of FF More, a typeface in fact built alongside FF Good to compliment it on the printed page – as well as on screen. 220,000 glyphs were all perfectly hinted for that purpose. Sets of Latin and Cyrillic Extended and all the figure styles that a typographer’s heart desires are included: lining, old style, proportional, tabular. No need to say more, FF Good is equipped for all eventualities. Just as much as the typefaces mentioned above FF Good stands out in the group of type design families.

It is a well-balanced system of distinctive parameters, of dimensions and of harmonious relationships – organized and consistent as well as warm and friendly. By these characteristics it will eventually set standards for new visual systems.

Footnotes

1. Zapf, Hermann/Jack W. Stauffacher: Hunt Roman. The birth of a type, Pittsburgh 1965, p. 20

2. Spiekermann, Erik: Adrian Frutiger. Schriften mit System, in: Studentenfutter. Ein Leitfaden durch den Buchstabendschungel, Nuremberg 1989, p. 99

3. Kelly, Rob Roy: American wood type. 1828–1900. Notes on the evolution of decorated and large types, New York 1977, p. 91

4. Maier, Thomas: Die Herstellung der Buchstaben. Wie Buchstaben für den Druck von Büchern hergestellt wurden und werden, dissertation, Linz 2009

5. Kelly, Rob Roy: American wood type. 1828–1900. Notes on the evolution of decorated and large types, New York 1977, p. 91

6. Ibid., p. 87

7. Maier, Thomas: Die Herstellung der Buchstaben. Wie Buchstaben für den Druck von Büchern hergestellt wurden und werden, dissertation, Linz 2009

8. Ibid.

9. Please read Majoor, Martin: My design philosophy, in: typotheque.com/articles (first published in: Tipografica, no. 53, Buenos Aires 2002)

10. Zapf, Hermann: Über Alphabete. Gedanken und Anmerkungen beim Schriftentwerfen, Frankfurt am Main 1960, p. 35

11. p. 36

12. Kelly, Jerry: Hermann Zapf at Ninety, in: Printing history. The journal of the American printing history association, new series, no. 6, 2009, p. 19

13. Frutiger, Adrian: Univers, in: Osterer, Heidrun/Philipp Stamm (ed.): Adrian Frutiger – typefaces. The complete works, Basel 2008, p. 88

14. Ibid.

15. Please read Spiekermann, Erik: Fürs Büro zu schade, in: Page, 6th year, no. 3, Hamburg 1993, p. 70–75

16. Frutiger, Adrian: Univers, in: Osterer, Heidrun/Philipp Stamm (ed.): Adrian Frutiger – typefaces. The complete works, Basel 2008, p. 88

17. Read more about Lucas de Groot’s Interpolation theory on: lucasfonts.com/about/interpolation-theory

18. Frutiger, Adrian: Univers, in: Osterer, Heidrun/Philipp Stamm (ed.): Adrian Frutiger – typefaces. The complete works, Basel 2008, p. 93

19. Ibid., p. 88

Bibliography and further reading:

• Aicher, Otl/Martin Krampen: Zeichensysteme der visuellen Kommunikation. Handbuch für Designer, Architekten, Planer, Organisatoren, Stuttgart 1977

• Bilak, Peter: Designing type systems, published on: ilovetypography.com, 2012

• Kelly, Rob Roy: American wood type: 1828–1900. Notes on the evolution of decorated and large types, New York 1977

• Lo Celso, Alejandro: Serial type families (from Romulus to Thesis). A thorough look at the history and development of large type families across the 20th century, published on: typotheque.com, 2004

• Maier, Thomas: Die Herstellung der Buchstaben. Wie Buchstaben für den Druck von Büchern hergestellt wurden und werden, dissertation, Linz 2009

• Majoor, Martin: My type design philosophy, published on: typotheque.com/articles, 2004 (first published in: Tipografica, no. 53, Buenos Aires 2002)

• Osterer, Heidrun/Philipp Stamm (ed.): Adrian Frutiger – typefaces. The complete works, Basel 2008

• Spiekermann, Erik: Mr. Univers, in: Typen & Typografen, Schaffhausen 1991